Are You There God? It’s Me, Jules

NOHspace, San Francisco

April 15, 2022, 7pm

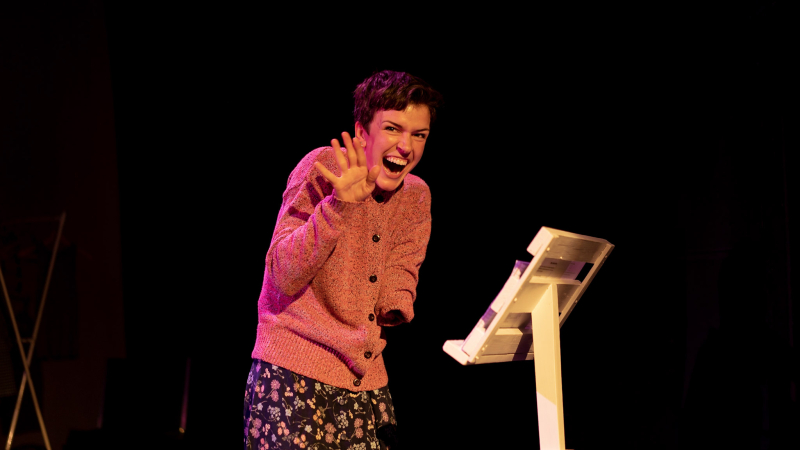

Choreographed and Performed by Julie Crothers

Original music by Ben Juodvalkis with contributions from Greta Hadley and Jeanne Hadley

Lighting design by Maxx Kurzunski

Review/response by Sima Belmar

I recently listened to a conversation between Wesley Morris and Dr. Daphne A. Brooks about the violence of lists like the Billboard Top 100, in which Brooks makes a strong case against canons in favor of care. In other words, it’s not about whether an artist or artwork deserves to be on a greatness or most popular list, but why a particular artist needed to make the work they made in a particular moment. In 2020, Julie Crothers was named one of Dance Magazine’s “25 to watch.” And though I agree that Crothers is indeed someone to watch, I’d rather follow Brooks and talk about what makes her work a work of this moment.

***

If you’ve ever identified as a teenage girl and grew up in the 1970s and 80s, you’re probably familiar with Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret, a novel about searching for religion, shopping for bras, and having to use pads held in place by a belt in the pre-adhesive tape era of sanitary napkins. Growing up in an interfaith household with a Christian mom and a Jewish dad, Margaret was spiritually lost—Jesus or Hashem? Christmas tree or Hanukah candles? Ham or gefilte fish? Though I grew up with two Jewish parents, I could relate to Margaret’s struggle. I prayed to the Jewish God of the Old Testament (mostly for the continued survival of myself and my parents, sometimes for Jordache jeans) in a combination of English and Hebrew, always signing off, “Thank you, God. Thanks an awful lot”—just like Margaret.

Given my intimacy with Blume’s book, Crothers’ title set me off chuckling before I’d even entered the theater, which was packed to the gills on opening night. Chuckles morphed into guffaws and gasps; my face hurt from smiling for an hour straight. Are You There God? It’s Me, Jules mixes sketch comedy, physical comedy, the multiple embodiments of the work of folks like Anna Deveare Smith and Sarah Jones, and dancing, exquisite dancing.

The performance begins with a land acknowledgment. Crothers’ took the form of a story, spoken in her own voice with a depth and care I rarely hear from white artists. She situates herself in San Francisco/Ramaytush Ohlone by way of Brentwood, TN, “a rich white suburb of Nashville, and ancestral home of the Cherokee, Shawnee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek peoples.” She talks about field trips to Andrew Jackson’s home and the way her American history education glided by slavery and the trail of tears, burial mounds and stolen land. In that way, her land acknowledgment is itself a performance of reckoning with erasure. She encourages us to find the QR code in the program that leads to The Association of Ramaytush Ohlone so we can donate funds. She takes her time. It was the first time in my experience that a land acknowledgment felt like more than lip service.

A phone rings in the audience. Jessi Barber answers so I know it’s a plant. (Later, my neighbor’s phone goes off—not a plant, grrrr.) Jessi says, “Hey Jules.” I can barely make out Crothers’ voice as she talks to Jessi from somewhere backstage. Jessi walks on stage, sets a clock for a 2-minute countdown. Crothers enters to an 80s sounding groove in her underwear and tank top, unfurls a long strip of tape on the floor diagonally in front of a clothes rack, and proceeds to set the stage: she repositions the clothes rack, a music stand, some chairs, a backpack, a bowl, a stool, three blue balloons, a water bottle, and sneakers. She dons red pants and a red blazer, and with ten seconds left, backs up to turn toward the audience before the alarm rings.

“Welcome. You are here and you are welcome here…” This is Jules the preacher and she is here to tell us a “true story” about God. With a convincing warmth that nevertheless borders on a kind of creepy kindness, the preacher explains that God has a big tv made up of billions of screens, one for every person—God is always watching. As she moves to a chair behind the tape, the preacher morphs into God himself: a dude on a chair with his leg up, watching tv and eating snacks, sometimes laughing, sometimes sighing at a cacophony of voices.

Crothers’ preacher returns to explain, “When you sin, God can’t see you. God can’t watch you sin.” She explains that the sinner’s screen becomes fuzzy. But then, “In comes JC with a wrench to save the day!” It’s hard to describe how convincing Crothers’ embodiments are, not because they aim for a sort of verisimilitude (there is no crown of thorns nor holy vestments), but because of the way her memory and imagination combine to create a kinesthetic expression. Jules as Jesus has her jacket tied around her waist and wears sneakers. Jules as Jesus who has come to fix everything is confident and smooth. Jules as Jesus makes imaginary nothing-but-net basketball shots and pumps her elbows, thrusts her pelvis. Jules’ Jesus is carnal.

This is the magic and mastery of Crothers’ performance, a layering of memory and imagination, of remembered and imagined embodiments, practiced and finely choreographed—even the improvised dance sections have a clear score and purpose: to embody character and affect, and to entertain. I believed every posture, gesture, vocal tone, and dance move. This would have been enough. But Crothers goes further by shaping a performance that also embodies the way Christian spirituality navigates, constructs, and claims transubstantiation. Crothers turns the teachings of her Christian upbringing into flesh. And she is clear that this is not entirely her own invention—her “Jesus dance camps” appear to have been centered around this very practice.

Crothers reenacts an experience from “Jesus ballet camp,” where she also studies “Jesus modern” and “Jesus jazz.” She describes a workshop that involved a tunnel maze on a “very intense Tuesday.” With a backpack on her back, she crawls through a chair (the tunnel) and tells us that the tunnel was covered in papers with sins written on them: anger, bitterness, boasting, divorce, drinking, dishonesty, hatred, homosexuality—as she pronounces each word, she shrinks, cowers, falls back as if burned, reminding us that, “If you don’t say it (or see it) it doesn’t count.” Emerging from the tunnel there is a bright light, a cross, and a dancer named Colleen. Jules tries to describe the feeling of the dancing and singing that follows the harrowing journey through the tunnel of sin, but she can’t find the words. Instead, she writhes as a rainbow (flag) lights the upstage wall and the Christian rock praise song she wrote with Juodvalkis and Greta Hadley, which Hadley sings, plays.

Because she always looks more or less like herself throughout the performance, it’s all the more extraordinary how Crothers transforms from preacher to God to Jesus to a painfully cheerful church mom to teenage Jules. As church mom, she recognizes faces in the audience, smiles, waves, and performs a shushing gesture. Like her play with transubstantiation, she uses verbal repetition to enact the ways dogma inscribes itself in the body but can also lose meaning. Church mom says, “I pray that you are moved. I pray that you want to be moved. I want you to want to be moved. I pray that you want to want to be moved.” To want, to move—the words change their meaning, lose their way. In this scene, JC returns like a boxer or bboy warming up to enter the cypher, sternum caved under the pressure of praying to want to want. I’m brought back to that Flashdance confession moment—” I want…I want so much!”

Crothers sets up her characters so the abstract dancing sticks to it; the dance sequences are coated in meanings established in the script, which allows her to maintain control of the character and the narrative even as it unspools, unravels. She appears always in command in part because she seems to be listening as she goes. It’s been said that acting is reacting and Crothers is right there, responding to (and delighting in) the unpredictable nature of live theater.

I could go on and on about the critique of Christianity Crothers performs in Are You There God? It's Me Jules. She certainly conveys the pain of shame around longing, particularly queer longing. But somehow critique feels beside the point. The point Crothers seems to be making is not a point at all but rather an ever-moving target of self-exploration. In the final scene, Jules is Jules. She calls God on a push button phone: “I’m sorry I ghosted you. You know. You don’t know? Ok.” Curled up in a chair, she wraps the phone cord around her toes, flanked by her props (what holds up our faith?). Ending on this earnest, teenaged Jules note is unexpected. It speaks to an evolving relationship with her faith and herself. Blume’s book is a coming-of-age story. Crothers’ performance is too but with the understanding (and promise) that she is forever a work in progress. I can’t wait to bear witness to the next phase.

Sima Belmar hosts the ODC podcast Dance Cast, teaches in the Department of Theater, Dance, & Performance Studies at UC Berkeley, and loves writing for Life as a Modern Dancer.

—

Related post:

5 Questions for Julie Crothers

——————-

Leave a comment